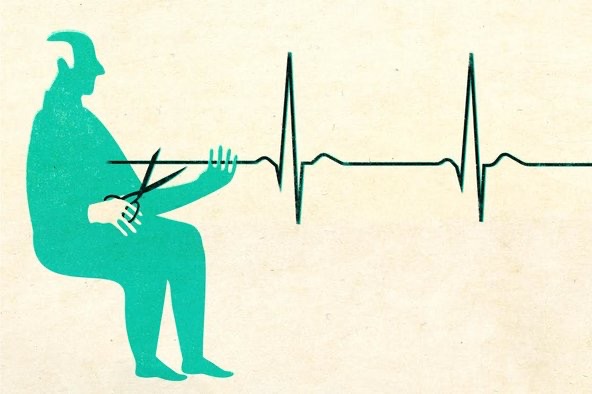

A Matter of Life and Death

Last week Delaware Governor Matt Meyer signed into legislation a law permitting physician-assisted suicide for terminally ill patients. “This law is about compassion, dignity, and respect,” the Governor said. “It gives people facing unimaginable suffering the ability to choose peace and comfort, surrounded by those they love.” On the Governor’s YouTube page, an emotional Mr Meyer makes the announcement in a halting voice, while scenes of sick patients and their families are intercut with those of the Governor.

Delaware - where I live - is the tenth state in the USA to authorize the termination of human life under special circumstances. By the way, “assisted dying” is not quite the same as “euthanasia”; the latter is where the doctor or nurse directly administers a lethal dose to the patient. “Assisted dying” is where the patient themselves take the lethal dose (already prescribed and authorized by the doctor). In both cases, the end result is the same.

The Delaware law comes into effect in 2026. There are a number of safeguards: those considering assisted suicide must be presented with other options for end-of-life care, including comfort and palliative care, and hospice and pain control. The state will require two waiting periods and a second medical opinion on their prognoses before the lethal medication can be prescribed to them.

The state of Delaware follows other states in legalizing assisted dying. Last year the Oregon Health Authority published a report about its own experience in implementing the Oregon Death with Dignity Act. The findings make for interesting and, at times, disturbing reading.

In Oregon, 75% of candidates commit suicide through ingesting a physician-approved cocktail of diazepam, digoxin, morphine, amitriptyline, and phenobarbital. A majority who have died are male, and 47% of the total number have a college degree of higher. 94% are white.

I had wrongly assumed that people who opted to die were in pain and probably in hospital or hospice care. However, in the Oregon survey, 88% of patients died at home. Only 28.8% of respondents cited “inadequate pain control, or concern about it” as a reason to die. A far larger number - 47% - instead cited “loss of autonomy, decreasing ability to participate in activities that made life enjoyable and loss of dignity.”

By sharing these findings, the Oregon Health Authority has, intentionally or not, raised serious questions about what value society places on a human life. Is loss of dignity a valid reason to be put to death? Are you no longer able to get out and enjoy life? Then maybe you should die.

The hidden subtext are the actions of family members who may wish to unburden themselves of the emotional and financial cost of caring for an elderly relative. What are the subtle pressures that a patient may experience from those closest to them? A well-meaning and sensitive patient may be persuaded by the arguments of close family members, and want to do the “right thing.” It has a grim logic, but is morally abhorrent.

Euthanasia and assisted dying are topics which present Christians, and indeed all people, with a moral dilemma. On the one hand, isn’t it merciful to prevent unnecessary suffering at the end of one's life, especially when there is no hope for recovery? If someone no longer wishes to live, then shouldn’t they be offered the option to die with “dignity”?

On the other hand, the sixth commandment forbids the taking of a human life. When human beings assume the right to decide whether someone should live or die, they are taking the place of God, for whom all human life has a meaning and purpose. Both the Episcopal Church and the Roman Catholic Church have condemned euthanasia as morally wrong, identifying its death-dealing practice as being in opposition to the life-giving nature of the gospel.

In 1995 Pope John Paul II published the encyclical Evangelium Vitae, which unequivocally opposed assisted suicide. He wrote that “any State which made such a request legitimate and authorized it to be carried out would be legalizing a case of suicide-murder, contrary to the fundamental principles of absolute respect for life and of the protection of every innocent life. In this way the State contributes to lessening respect for life and opens the door to ways of acting which are destructive of trust in relations between people.” (72)

This is a slippery slope. As we have seen so often in the past, legislation is passed with restrictions and later the restrictions are loosened or even removed. Across the border in Canada, where medical assistance in dying has been legal since 2016, an astounding one in 24 deaths there is attributable to assisted suicide. Once this idea enters the cultural milieu and is promoted and legislated for by the state, it is very hard to dislodge.

By legalizing assisted suicide, the state of Delaware is acceding to the principle that human beings can judge for themselves what constitutes a good life and what doesn’t. While reasons can be made for justifying assisted suicide, in the end the decision is purely subjective. In this regard, it is interesting to note one other statistic from the Oregon survey: of those prescribed life-ending medication, 15% chose not to take it.

One of the questions this topic raises had to do with the value of suffering. No one wants to suffer. Generally speaking, society chooses medical means to remove or alleviate suffering, both physical and psychological. Yet suffering was also the way of our Lord and is intrinsic to our understanding of life and faith. Seeing suffering in purely negative terms diminishes it as the way to enter into a deeper relationship with Christ, the suffering servant.

This is not an argument in favor of prolonging suffering or avoiding a natural death. Evangelium Vitae is careful to distinguish between euthanasia and the natural end of life: “when death is clearly imminent and inevitable, one can in conscience ‘refuse forms of treatment that would only secure a precarious and burdensome prolongation of life, so long as the normal care due to the sick person in similar cases is not interrupted.’” (65)

We must not lose sight of the fact that assisting someone to end their life, whether you are a relative, nurse or physician, makes you complicit in killing. For this reason, it will always be a moral question. It asks questions about how we view human life: are the decisions I make about my life purely subjective - I know what’s best for me - or do they impact upon those around me? What role does love play in these decisions? What is a loving response to someone who wants to kill themselves?

The values of the world do not always align with those of heaven. Human life to God is precious and God is present to us at all times, even in our darkest hour. For God, our primary meaning is intrinsic to who we are, and is not based on any utilitarian understanding. At the core of this is love and relationship. For those considering suicide, the question is, “is this what God wants for me?” And for close family members and friends, the question is, “am I honoring both God and this person in supporting their decision?”

If you can imagine yourself reaching this position one day, then my advice is to start thinking now about the value of your own life and your relationship to God. By relying solely upon your own judgment, or upon the judgment of others, you may make the wrong decision. In prayer you can begin to order you life aright now, and be ready to make the right decision when the time comes.

Yesterday I was in the chapel for Evening Prayer, and prayed for the Church, the world and for all who are in need. I had been thinking about the question of assisted suicide when these words from the prayer leapt off the page. They make a suitable conclusion to this meditation: “That those who suffer pain and anguish, may find healing and peace in the wounds of Christ.”

Father David

0 Comments

There are no comments.

Stay Tuned

Sign-up for David's newsletter